Reflections on America's History

How a road trip through Pennsylvania and Ohio captures America at its best and worst

I’m on the road (again!)—this time a solo car trip to Michigan. I took a leisurely drive here from Virginia, had dinner with friends in Ann Arbor, visited more friends in the Jackson area, and am now Up North, that portion of Michigan referred to as the “Tip of the Mitt” (if you’re not familiar with Michigan geography, think about it—you’ll get it). I’ll be sharing more about this adventure in future posts, especially about my first tent camping experience in probably thirty years! Michigan is a stunningly beautiful state. I’d almost forgotten how lovely it is.

But I’m going to start today with reflections from my second day on the road through Pennsylvania and Ohio—the hardest emotional day of the trip. In some ways, this day provided a transition from a world overrun with negative news to the natural beauty I hoped to encounter. These stops were especially timely as we honored the 24th anniversary of 9/11 last week at the same time as we witnessed the presence of armed National Guard troops in our cities, political assassinations, and attacks on free speech.

America Attacked - Shanksville, PA

The sign says that to hear the wind chimes the wind must be blowing at 15 to 20 mph. On this calm September day, only a flock of Goldfinches interrupted the solemness of the space. The 93 foot tall wind chimes, respectfully named The Tower of Voices, were silent, much like the voices of the 40 heroic people who died on September 11, 2001, when their plane crashed into this Pennsylvania field (listen to the chimes here).

As the sun peeks over the surrounding trees, I scan an area awash with wildlife. A family of wild turkeys with a brood of at least fifteen baby chicks scrounges for treats on the side of the road. A herd of eight whitetail deer grazes peacefully in the once assaulted field. A flock of Canada geese squawk overhead, circle the field, and land in a nearby marsh.

I’m not used to being up and out at sunrise. It seemed like today was one of the days when I needed to be. The people on Flight 93 had risen much earlier—long before the sun peeked over the horizon—to board their 8:00 a.m. flight in Newark on their way to San Francisco. When they did, they, of course, had no clue that this would be their last sunrise.

At 10:03:11, United Airlines Flight 93 crashed into a field near a reclaimed coal strip mine. Local residents of Shanksville said that the sound of the ill-fated plane was deafening as it roared much too close to their homes. I wonder what the deer, turkeys, Canada geese, and all the other creatures that call these fields and woodlands home heard that day. How many of them also died in the crash? As far as I know, no one ever countered them among the dead.

Upon leaving the Tower of Voices, I park at the Memorial Plaza and Crash Site. There I walk alongside the field that had been assaulted by hijackers. The site of the crash is marked with a large rock, a 17.5-ton sandstone boulder. This boulder was placed in 2011 at the boundary of the impact site as a memorial to the passengers and crew who fought back against the hijackers.

Paul Murdoch Architects and Nelson Byrd Woltz, Landscape Architect, who designed the memorial, said they knew visitors would want to know the exact place of impact. They were right. I wanted to know. There was something bizarrely settling in knowing, in seeing, the exact spot where the massive plane collided with the earth.

A surviving grove of Hemlock trees stands strong along the edge of the crash site. It serves as a reminder that like these trees bound together by a shared root system, the passengers of Flight 93 are united by their shared destiny.

A wall of names adjacent to the field honors the intrepid forty. Between the wall and the rock is a Ceremonial Gate, which only family members and park officials are permitted to cross to enter the impact site. The gate is constructed from hewn hemlock beams with forty cut angles, one for each passenger and crew member who died.

The walk from the Memorial Plaza to the Flight 93 National Memorial Visitors Center resembles the sacred ground of a battlefield. This is by intention. The designers wanted visitors to remember the gravity of what happened here. The approach to the Visitors Center takes visitors on the direct path of the flight as it descended into the field.

Of all the displays telling the story of the flight and its aftermath most moving to me are the audio recordings of voice mail messages left by two passengers and a flight attendant to their families. The first passenger tried to comfort those who were listening by minimizing her fear “A little something’s happening on my flight,” she said, her voice shaky and weak. She told them she loved them, but she didn’t want anyone listening, expect perhaps the people who knew her well, to know how serious the situation actually was. They soon found out.

Another woman starts out calm while reporting there were hijackers on the plane but then bursts into tears. She recovers enough to share, in a matter of fact way, the combination to the safe in her bedroom closet, where she keeps her important papers.

The third recording, this one from a flight attendant, clearly states, in a voice much like she might instruct passengers to prepare for landing, that the plane had been hijacked,. She said she is trying to remain calm but also says her goodbyes because things don’t look good.

I can’t even begin to imagine receiving a call like that—the desperate helplessness that would follow it. Did the families already know what had happened when they listened to the messages? Or was this their first clue? I imagine their anguish either way.

Despite the conspiracy theories surrounding them, the 9/11 attacks will always be a watershed moment for the people of the United States. For a day, a week, even as long as a month before the retaliatory attacks on Afghanistan, we came together as one people, united in our identity as Americans.

As I drive away, tears well up inside me. Would we ever again feel as interconnected as we did after being attacked? Why does it take a horrific event such as this to come together? If something like this happened today, would we be as united? The answers elude me as I ponder what it means to be an American and continue my journey.

A Different America – The Lincoln Highway and Mr. Rogers

After leaving the Flight 93 Memorial, I meander along US 30, know as the Lincoln Highway, the first transcontinental highway in the United States, designed in 1913 specifically for automobiles to drive from New York City to San Francisco. I stop at the Lincoln Highway Experience, a visitors center in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and, with unbelievable willpower, resist the piece of homemade apple or cherry pie included with my admission fee.

While there, I examine photographs of quirky roadside attractions, like the Coffee Pot restaurant, shaped like a giant coffee pot, Haines Shoe House in York, a five-story building shaped like a giant boot, and Mister Ed’s Elephant Museum & Candy Emporium in Orrtanna, featuring a life-sized elephant statue named Miss Ellie and over 12,000 elephant figurines.

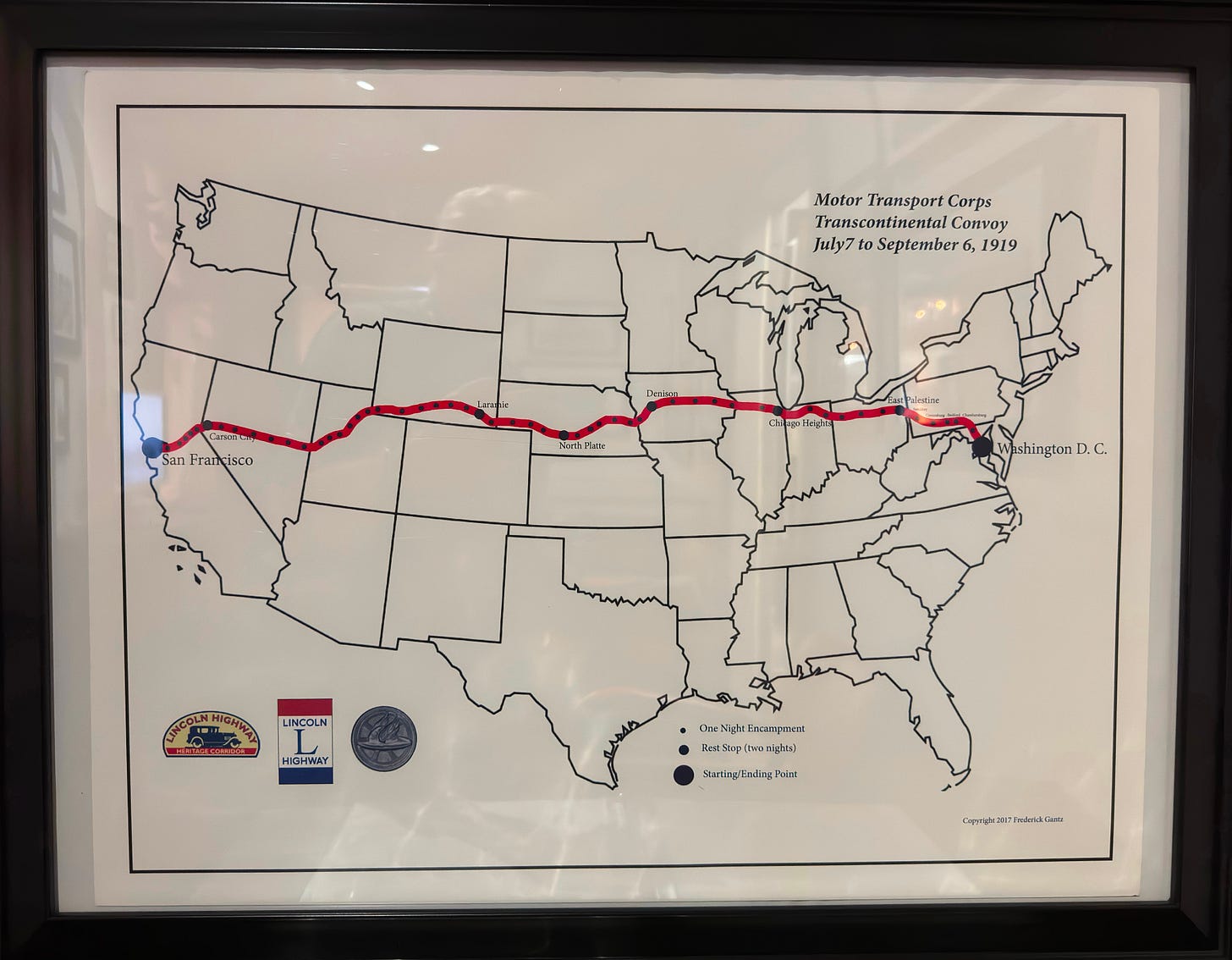

I see images of then Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower, who in 1919, made the arduous 3,000-mile journey as part of a military expedition, The First Transcontinental Motor Convoy. The challenges he encountered on this journey—muddy, rutted roads, broken bridges, frequent mechanical breakdowns, and slow progress that sometimes required soldiers to push or tow vehicles by hand— served as inspiration for his support of an interstate highway system and the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956.

As I drive this iconic road, I imagine a different America, a different world, than the one that made 9/11 possible. My imagination, or should I say my longing, for a different America peaks a few miles down the road from the Lincoln Highway Experience when I stop at the Fred Rogers Institute at St. Vincent College. Yes, that Fred Rogers! Apparently, he was born in Latrobe and referred to it as his “first neighborhood.” I was a little too old for Mr. Rogers Neighborhood, which started in February 1968. I knew, however, that he stood for peace, so I stop to pay my respects.

In touring the exhibits about his life, I fumble with the video screen that ran video clips from iconic Mr. Rogers shows. Without intentionally selecting it, I watch Mr. Rogers in a prime-time show addressing parents after the Robert F. Kennedy, Sr. assassination. In it, he expresses alarm over the unfiltered violence children were exposed to through the media, stating,

I’ve been terribly concerned about the graphic display of violence which the mass media has been showing recently. And I plead for your support of your young children. There is just so much that a very young child can take without it being overwhelming.

Who, I wondered, could say those things today and be taken seriously? And, at the same time, I longed to hear his voice speaking to all of us about today’s news.

America Attacks – Kent State University

My final stop of the day took me to Kent, Ohio. I’ve long intended to visit Kent State University but whenever I passed nearby, I decided I was in too much of a hurry to stop. Today, I want to rectify that.

Kent State is the site of the May 4th (1970) massacre when the Ohio National Guard opened fired on peaceful protestors. Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller joined three hundred others on Kent State’s campus protesting the expansion of the Vietnam war’s Cambodian campaign. Two other victims, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder, were observing the protest between classes.

Twenty-eight National Guard soldiers fired 67 rounds over 13 seconds at unarmed students who stood no closer than 60 and as much as 400 yards away from them. In addition to the four who died, nine other students were wounded that day—one of these permanently paralyzed. These young people stood up for peace and were gunned down, not in Vietnam, but here on a college campus in the United States.

As I park my car and look around, I try to remember news reports of the day to place the National Guard troops and the students they were trying to control. I remember a hill, but I can’t remember if the guardsmen shot up the hill or down it. Only after a reading the historical markers, make a stop in the visitors’ center, and have a chance encounter with Dr. Sara Koopman, Assistant Professor in the School of Peace and Conflict Studies, could I envision the scene as it unfolded.

Dr. Koopman describes herself to me as a geographer with a focus on peace. Who knew such a specialty existed? I certainly didn’t. Sitting on a park bench adjacent to the concrete memorial talking with a student, she interrupts her conversation to point out to me that the students’ names are not on the memorial itself, but rather on a plaque in the ground hidden underneath some bushes. This clearly doesn’t please her.

I ask Dr. Koopman how today’s Kent State students are dealing with seeing National Guard troops roaming our cities. She tells me that most students walk by the memorials every day and either don’t know what happened here or don’t give it another thought. She’s working hard to change that, but it’s an uphill climb.

Even after my conversation with Dr. Koopman, who has created an app that marks key sites and includes statements from those who were there that day, it takes me several tries to locate the markers placed at the exact spots where each student fell. That’s because they died in a parking lot and, without close inspection, the concrete markers look like they were placed there for utility access of some sort.

After I know what I’m looking for, I make a point of visiting and photographing each one.

The National Park Service states:

This site is considered nationally significant given its broad effects in causing the largest student strike in United States history, affecting public opinion about the Vietnam War, creating a legal precedent established by the trials subsequent to the shootings, and for the symbolic status the event has attained as a result of a government confronting protesting citizens with unreasonable deadly force.

When I raise my concern with Dr. Koopman about the Administration’s attacks on history and whether they would try to remove Kent State’s designation as a national historic site, she acknowledges that she hadn’t heard anything yet. “We’ll see,” she said, “there’s no telling.”

As the sun slipped lower in the sky, I know I still have a ways to go to my hotel in Cuyahoga Falls, so

I do not take the time to find the newest markers that Dr. Koopman told me were just installed in 2021 to honor the nine “blood brothers” who were wounded that day. They’ll have to wait for another visit.

Heading to my final destination for the night, I express my gratitude to the universe for the freedom I have to travel and for the incredible people who have kept and are keeping these stories alive. I also say a prayer that the forty people who died in Shanksville, those intrepid souls who built the Lincoln Highway, Fred Rogers, and the killed and wounded at Kent State will never be forgotten.

I hope you’ll make a similar pilgrimage one day. It matters that we remember.

Thanks Annette for sharing such an amazing journey. I could feel the emotion shared by your observations. Peace

Thanks in particular for the reflection and photos of Flight 93 memorial, Anette. It's still tough for me too, 24 years later.