Road Trip Episode 5, Part 2: A Lesson in Privilege

In Part 2 of Road Trip Episode 5, I explore how recognizing my assumptions about who I am and the privilege I carry taught me an important lesson.

In Road Trip Episode 5, Part 1: The Road Not Taken, I describe my route from Minneapolis to Winnipeg and how my choice not to take “the one less traveled by,” might have impacted my travel plans. Today, we begin at the Pembina–Emerson Border Crossing between North Dakota and Manitoba.

Screening

“What’s your business in Canada?” the border agent began.

“I’m visiting a friend in Winnipeg,” I replied.

“How long you staying?” he continued.

“A week,” I said.

He carried on with more of what I considered standard questions. “How many people in your vehicle?” “When’s the last time you visited your friend?” “Why are you visiting her now?” “Are you bringing in any gifts or other merchandise?”

It was his next question—a question I’d never been asked before—that elevated my heart rate and I’m sure my blood pressure followed. “Have you ever been fingerprinted?” he inquired, turning his full attention to me now, looking at me with eyes squinting against the glare of daylight outside his tiny booth.

As he did, I was immediately transported back thirteen years to Phoenix, Arizona. I could feel the Maricopa County Sheriff Deputy release the handcuffs that squeezed my wrists together behind my back. I could feel her rough fingers as she grabbed my right hand. I recalled how helpless I felt as she guided my hand to the desk in front of me, pressing my right thumb onto an ink pad and then rolling it on the fingerprint card with my name on it sitting on the desk. I remembered thinking how smoothly she repeated the process nine more times with each finger while I stood there in her control. I remember feeling a strange sense of relief when she secured the handcuffs again and ordered me to sit down on the bench against the wall behind me.

Should I lie and say “no?” Did he have a database connected to my name that showed my fingerprints or was this a standard question that they randomly asked? I decided I’d better tell the truth.

“Yes,” I answered.

“When was that?”

“2010”

“What for?”

“I was arrested,” I offered, somewhat more meekly than I expected.

He glared at me, “What were you arrested for?”

My brain froze. I didn’t consider how my answer might be received, I just answered. “Civil disobedience,” I said. He scowled and then refocused his attention on his computer screen.

What came out of my mouth wasn’t exactly truthful. I wasn’t arrested for civil disobedience. I was arrested for being part of a group of demonstrators who blocked an intersection. That was the charge: blocking an intersection.

We were protesting Arizona’s anti-immigrant law, SB 1070, which, ironically, given my current situation, required everyone, regardless of citizenship status, to show their papers when asked by police officials.

I spent 26 hours in the infamous Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s jail before being arraigned and then released on my own recognizance. A shiver ran down my spine as I remembered the cold concrete block walls of the cell that they crammed fifty protesters into, overwhelming the regular prisoners there for processing.

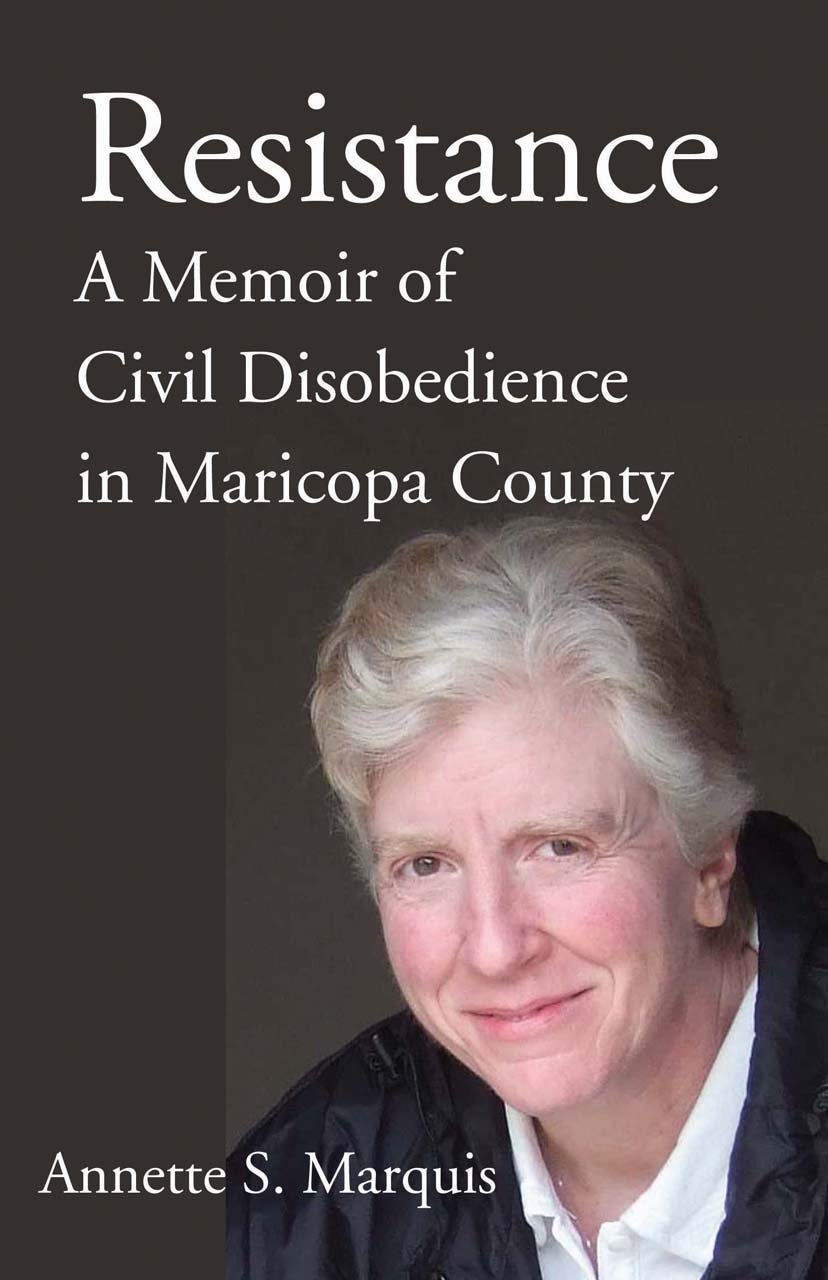

I wrote about my experiences in my 2013 memoir, Resistance: A Memoir of Civil Disobedience in Maricopa County. It is not an incident I care to repeat, but you can read about it here.

While I waited for the border agent to resume his questioning or pass me through, I reminded myself that the worst they could do is deny entrance to the country. Right? Could they arrest me for something? I didn’t think so, but… Did my close-cropped hair that hadn’t grown out after losing it to chemo this summer put him on alert? Did I look like an escaped convict? Or maybe a soldier fleeing into Canada after going AWOL? I considered all the possibilities. After a few tense minutes, he spoke again.

“Do you have any weapons, firearms, knives?” “Do you have any mace, pepper spray, tasers, bear spray…” It seemed like the list went on for a long time, so I’m sure he asked about more weapons. I’m just not sure what else could have been on his list. I answered “no.”

He then directed me to roll down my rear window. I did. He nodded and I rolled it back up. Nothing to see there.

Just when I thought he would say, “You’re free to go,” he directed me to pull up into the spot marked B, as he pointed to my left. “Go inside and give them this.” He handed me a white half-sheet form filled with what appeared to me to be indecipherable codes.

“Oh, shit,” I mumbled. I quickly assessed the things in my car. I reassured myself that, if they searched it, they wouldn’t find anything illegal. I could at least breathe easy about that.

I did as he said. My one regret is not taking a picture of the form, so I could have examined it later. Maybe it would have provided a clue to their suspicions. Instead, I gulped, feeling genuine fear for the first time. Were they going to prevent me from entering Canada because I’d been arrested? Because I was an agitator? Because I had a few left-leaning bumper stickers. Because I’m a lesbian? Did they think I was coming to cause trouble. Did they think I was planning to immigrate illegally? Did I drive all this way only to be turned back? What the hell!

The questions swirled in my head as I opened the car door. I swung out of the driver’s seat and planted my feet on the ground in this in-between place—a demilitarized zone of sorts—not the U.S. any longer, but not quite Canada yet. Taking a deep breath, I headed into the building.

Interrogation

I handed the unintelligible form and my passport card to the young man behind the counter. He asked my name and address and maybe a few other things that I don’t remember, before saying, “Sit over there and wait for an immigration officer to talk with you.”

“I’m not immigrating,” I corrected him. “I’m just visiting.”

“Sit over there,” he repeated without responding.

I remember feeling thankful that I didn’t have handcuffs clenching my wrists behind my back as I sat.

I waited for what seemed like eternity, but was probably only a few minutes, before a uniformed woman, her hair pulled back tightly behind her head and no smile on her face, came to the counter. Even though I was the only person in the room, she called my name. I approached.

Again, she asked my name and address while examining my passport card. Then, “What states have you lived in?”

“Let’s see,” I began. “Virginia, North Carolina, Michigan, Massachusetts, Illinois, and Colorado.”

She continued with her questions without responding. “Where were you born?”

“Ann Arbor,” Before I had a chance to say “Michigan,” she asked a different version of the fingerprinting question, “Have you ever been arrested?”

I took a breath and said, “Yes.”

“What for?”

This time, having had more time to think about it, I gave a more accurate accounting, leaving out the civil disobedience part. “For blocking an intersection,” I said. She looked at me, clearly bemused. I’m sure her confusion was the same as mine when I first heard the charge. How does a person block an intersection?

“Did you get a traffic ticket or go to court?” she mumbled without looking up.

“They dropped the charge before I went to court,” I responded. I didn’t tell her the rest. The prosecutors lost the first three cases against the protestors because the court determined that a person can’t really block an intersection, especially after the police had already done so with cars, vans, and other emergency vehicles in preparation for the anticipated protest. They dropped the charges against the remaining defendants, me included. I never had to go to court.

Perhaps deciding I was not a hardened criminal, but still concerned I was up to nefarious things, her focus changed to the friend I was visiting.

“How long have you known your friend?” “How did you meet?” “What’s her name?” “Where does she live?” “What’s her occupation?”

I expected her to ask whether she’d ever been arrested, or whether she engages in protests, but she didn’t go there.

Eventually, she said, “Go have a seat while I check out some things.”

I did as she said, sitting in the ominously empty building’s hard plastic chairs for the second time. What was she checking? What databases was she now accessing to search for my name?

As I sat there, I reviewed her questions and my answers. “Oh, I forgot to tell her Arkansas,” I shouted out to the young man behind the counter. “I grew up in Arkansas.” How had I forgotten that one?

He didn’t seem to care.

Release

Finally, she re-emerged, handed me my passport card, and said the words I’d been waiting for, “You’re free to go.”

I could feel the breath escape from my body. I closed my eyes for a brief second, and then couldn’t hold myself back. I had to know. “What was this about?” I asked.

She flinched just the tiniest bit. “Just an immigration check,” she replied, clearly surprised by my boldness.

I left it at that. I didn’t expect to get more information from her after all she had extracted from me. I exited the door I came in, re-entered my car, and then just sat there.

When I had collected myself, I looked at my watch. What had seemed like hours was, in reality, only minutes—less than thirty minutes had passed since I calculated my ninety-minute drive to Winnipeg. I started the engine, backed up, and rejoined the highway—this time on the Canadian side of the border.

Reflection

As I drove the remining miles to Winnipeg, I thought about the people who have given up everything to attempt what I had just done--cross a border into another country. I thought about the millions of people (Yes, millions! 2.2 million people were apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border in the first nine months of 2023!) from countries near and far who walk for endless miles, deal with unscrupulous coyotes, cross a raging river, and traverse a hostile desert in search of a better life in the U.S.A. All of them, especially those who don’t have my white skin, my gray hair, my level of affluence, my education, my English-language fluency are greeted with suspicion, as I had been. But truth be told, I had little to fear.

If I’d been denied entry, I would have been certain that it was an error. I would have called my friend, who would have called her friends and family, who would have known an immigration attorney, who would have rectified the immigration officer’s clear mistake, and I would have gone on with my travels. Or, if it couldn’t have been resolved quickly, I would have asked my friend to drive ninety minutes to the border and cross into the States, so that we could enjoy our time together on my side, until things got figured out.

My fear in the moment was understandable, but not comparable. Was I surprised that I wasn’t recognized for my status and allowed in without question? Absolutely. I move in a world of privilege, and I expect the world to treat me with a certain deference. I can’t deny that.

That being said, I deeply believe that all people deserve to be treated with the same respect and dignity I receive every day. This experience only served as a humbling reminder of how much work we have to do, that I have to do, for that to be true.

My prayer is that my country finds it in its collective heart to respect the human rights of asylum seekers and refugees, that we set aside our fears and open ourselves to better understanding the genuine fear that people who risk everything to immigrate experience, and that we live our lives guided, not by fear, but by love.

Thank you for reading. I’d love to hear whatever thoughts this piece brought up for you.

It says a lot about you that you have the insight and self-awareness to put yourself in the context of the wider world. It's one of the many reasons I love you!

Excellent piece! Beautiful connections to your experience and the the experiences of many others and of our times... "the story of self, the story of us, the story of now" as Marshall Ganz writes. Also appreciated learned about St. Cloud, MN!