Road Trip Episode 4: The Power of Naming and Knowing

In this essay, I take you to the Lake Superior shore in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where I learn a lesson in the power of naming and knowing.

The southern shore of Lake Superior in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan is one of my favorite places on the planet. The “Graveyard of the Great Lakes,” the part of Lake Superior between Grand Marais and Whitefish Point, has a history of churning up ships like they’re made of balsam, and just a little further to the west, transforming coastlines into colorful sandstone cliffs so beautiful they’re called Pictured Rocks.

The northern hardwood forests, or Northwoods, wrap the largest freshwater lake in the world in a blanket of American beech, sugar and red maple, yellow birch, hemlock, and white pine trees that tower over its shores.

As I stepped out of my car into a forested patch near the lake’s stunning shoreline west of Marquette last month, the aromas of sweetfern, balsam poplar, and pine combined to remind me that I was home. Nothing smells so fresh, so alive, as the Northwoods.

As a late teen, I moved back to my birth state of Michigan. It was then I fell in love with the Northwoods. Even though I lived a couple hours south of the official start of the ecoregion called the Northwoods, they called to me, and I routinely found myself answering their call. Eventually, I purchased some land in the northwestern lower peninsula of Michigan near Traverse City and a few years later called the Northwoods home.

There, with the help of a local farmer and homesteader named Elmer, I learned to identify the various types of trees that made up the forest. I examined the shapes of pines, spruces, firs, and junipers. I learned their needles and pinecones. I studied the bark of aspens, paper birches, mountain ash, and maples and learned to recognize them from a distance.

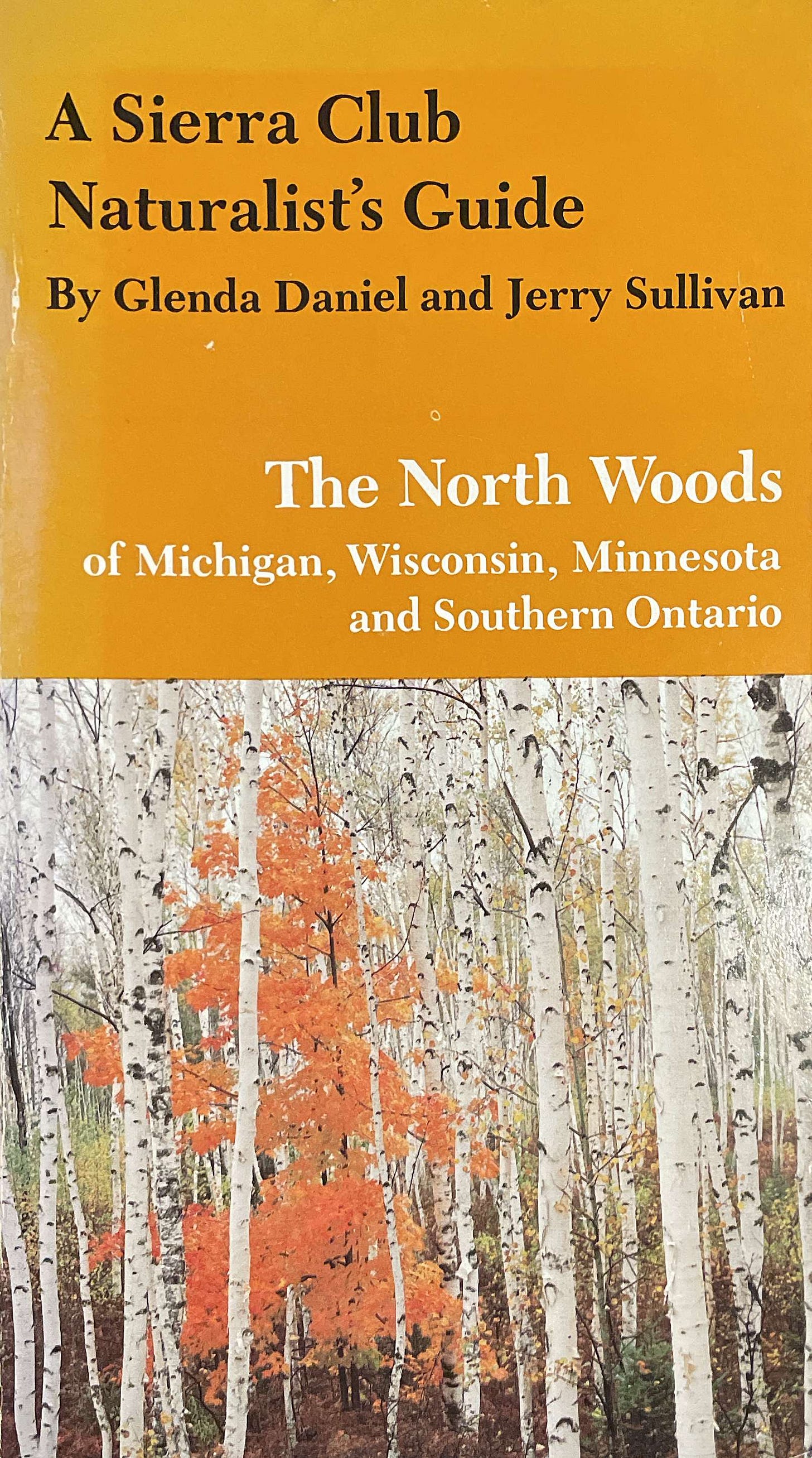

I treated the Sierra Club Naturalist’s Guide by Glenda Daniel and Jerry Sullivan, The North Woods of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Southern Ontario as if it were a sacred text. I devoured the information in this 400-page tome about geology, plant life, and animals that thrived in the region.

And just like Meg in Madeline L’Engle’s A Wind in the Door, I learned that naming helps parts of creation learn how to be themselves. It’s a recognition of our interdependency and interrelatedness. Through this deepening understanding, I developed a deep love for the Northwoods and knew they loved me back.

The secrets of the atom are not unlike Pandora's box, and what we must look for is not the destructive power but the vision of interrelatedness that is desperately needed on this fragmented planet. We are indeed part of a universe. We belong to each other; the fall of every sparrow is noted, every tear we shed is collected in the Creator's bottle.

— Madeleine L'Engle, The Rock That is Higher: Story as Truth

The unidentified tapestry

I grew up in the hills, ravines, and forests of the Ozark Highlands in Northwest Arkansas. This was my playground as a kid. If I wasn’t shooting a basketball into the hoop hanging off our second story porch, I was in the ravine behind our house, climbing rocky cliffs, or exploring Lake Atalanta and the bubbling creek that fed into it.

I loved being in the woods, and I spent as much time as I could there climbing, exploring, rock scrambling, and crawdad hunting. The woods and creeks taught me self-reliance and independence.

I was not (am not) a particularly brave explorer. I didn’t often swing on the massive vines that hung from trees at the bottom of the ravine for fear of letting go at the wrong time and crashing to the forest floor below. I liked climbing up the rock cliffs at the base of the ravine but hesitated going down them for the same reason. Although other kids seemed to have no problem using an old log like a balance beam to traverse the creek, my heart would race and I’d freeze up at the mere thought of slipping into a den of water moccasins that frequented that part of the creek.

But despite my fears, I felt freer in the woods than in any other part of my life. I could wear old clothes, get dirty, and not worry about what anybody thought. I could do what I wanted, go where I wanted, and nobody could stop me. The woods represented beauty, mystery, challenge, and autonomy.

I regret now though that I never learned the names of the trees and other plants I romped passed on my way to my next adventure. The only tree I really knew during my childhood was the majestic white oak that stood at the end of our driveway. I would watch the cardinals dart around its branches and be thankful they had such a wonderful home in which to raise their young.

I didn’t know then about the 900 species of Lepidoptera (moths, butterflies, and skippers) that, according to Doug Tallamy, author of The Nature of Oaks, also call the white oak home. I just knew that when I saw that old oak tree, I felt at home.

Other trees were just trees—some tall, some stout, some craggy, some stately—part of the tapestry that made up the forest. Regretfully, it never crossed my mind to learn more about them.

That’s why it mattered so much to me when I finally learned some of the names of the trees that made up the Northwoods. Although I loved playing in the Arkansas woods, I never felt the indescribable connection to them that I feel when I’m in the Northwoods.

The gift the comes from knowing

As I drove through northern Minnesota and Wisconsin and then into the Upper Peninsula on my recent journey, I started grieving the dead and dying trees I saw. Miles of yellowing needles and bare trunks convinced me that something was killing the conifers in my beloved Northwoods.

I stopped to take illustrative photos and then when I returned to the car, my heart ached with sadness. I felt helpless—like losing a friend to terminal cancer.

When I reached my hotel that night in Marquette, I began researching what could be causing so much destruction. I had convinced myself that the global climate crisis was to blame. Although I saw references to infestations of southern pine beetles heading north due to climate change, I didn’t find anything definitive. “Why isn’t this being written about?” I shouted aloud in my empty hotel room, cursing the internet in frustration.

On the phone that night I said to my wife, Wendy, “I’m devastated by the damage I saw. Large swaths of my forests are dying.”

I went on, “At first, I thought the yellow-leafed trees were just showing their fall colors, but then when I looked closer, I saw they were evergreens. Something is killing them!” I moaned.

Wendy did her best to comfort me, but she knew there was little either of us could do.

When I returned home, I did more research so I could write about this horrible disease that was killing my dear friends. That’s when I discovered my error.

What I had encountered was not mass extinction but instead the annual ritual of the tree that, Rick Meader, a Michigan landscape architect, refers to as the “conifer that dares to be different.”

Tamarack trees, also called Eastern Larch (Larix laricina) lose their needles in the fall when deciduous trees lose their leaves. Tamaracks turn brilliant gold before their short, soft needles cascade to the earth below. They are diversity personified!

Had I taken the time to know Tamarack trees, had I been able to name them—to distinguish them from other conifers and understand their needs—I would have known that what I was seeing was not extermination by some virulent assailant but, instead, the normal cycle of life.

I’m thrilled to know that these massive trees will survive the harsh winter, regrow needles in the spring, and stand proudly with other conifers throughout the summer until it’s time to lose their needles once again next fall.

Whether our family members are other humans or part of the larger interconnected network of nature, we can’t know everything about each other. But we must be open to learning. We have to take the time to fully embrace each other by understanding the habits and characteristics of the other — rejoicing when they prosper, celebrating their changes, and mourning when they get sick or die.

I’m embarrassed by my assumptions (I’m sure there’s another essay in that), but at the same time, delighted that I took enough time to learn that I had misinterpreted what I saw.

Naming what you see

It’s clear that I have a lot more to learn about the Northwoods, and since I now hail from Virginia, the opportunities are fleeting. That’s why I do what I can to learn about the trees and plants that are native to the Piedmont region of Virginia, the ones that make up the forests along the James River and that grow in my own tiny piece of earth.

But nothing will ever replace the feeling I get when I breath in the Lake Superior shore and the flora and fauna that’s fed by it. It will always be home.

Loved reading your descriptive writing on Lake Superior!! The way you describe your travels through MI brings back memories from our trip! The way u wrote about the Tamarack Trees built up anger and then relief as you became more knowledgeable about their history! Great writing!

I feel that I’ve come home when I enter the San Francisco Bay Area. Even though not indigenous, I feel like I’ve come home when I breathe in deeply the eucalyptus. When I see the mighty pines, and feel the fog’s mists on my face. And like when my heart slows as I walk into a room of impressionist paintings. I come back to being centered in myself again. Thanks for your story that reminded me of mine.