By the time Joanne became a teenager, she had been arrested too many times to count. No, she wasn’t a juvenile delinquent, although some might have considered her one. Instead, she was a freedom fighter, a child of Selma, Alabama, who joined the fight for civil rights when her grandmother told her she couldn’t get ice cream at the drug-store counter until Black people like her won their rights.

Joanne has lived her life fighting for her rights and inspiring others to do the same. From marching on Bloody Sunday—that iconic day in 1965 when protesters, including John Lewis, Amelia Boynton, and Joanne’s older sister Lynda, were battered and beaten in one of the first televised episodes of state-sanctioned violence to founding the National Voting Rights Museum—Joanne has been a life-long freedom fighter.

After retiring from a career in the Army, Joanne returned to Selma to make sure that the important civil rights history of her beloved and beleaguered city would not be forgotten. She formed a tour company called Journeys for the Soul to share the role Selma played in the Voting Rights Movement. Most recently, she has founded a multi-million-dollar project called Foot Soldier Park. This project will not only commemorate the thousands of people who played a part in the Movement but also to “nurture the next generation of social justice activists.”

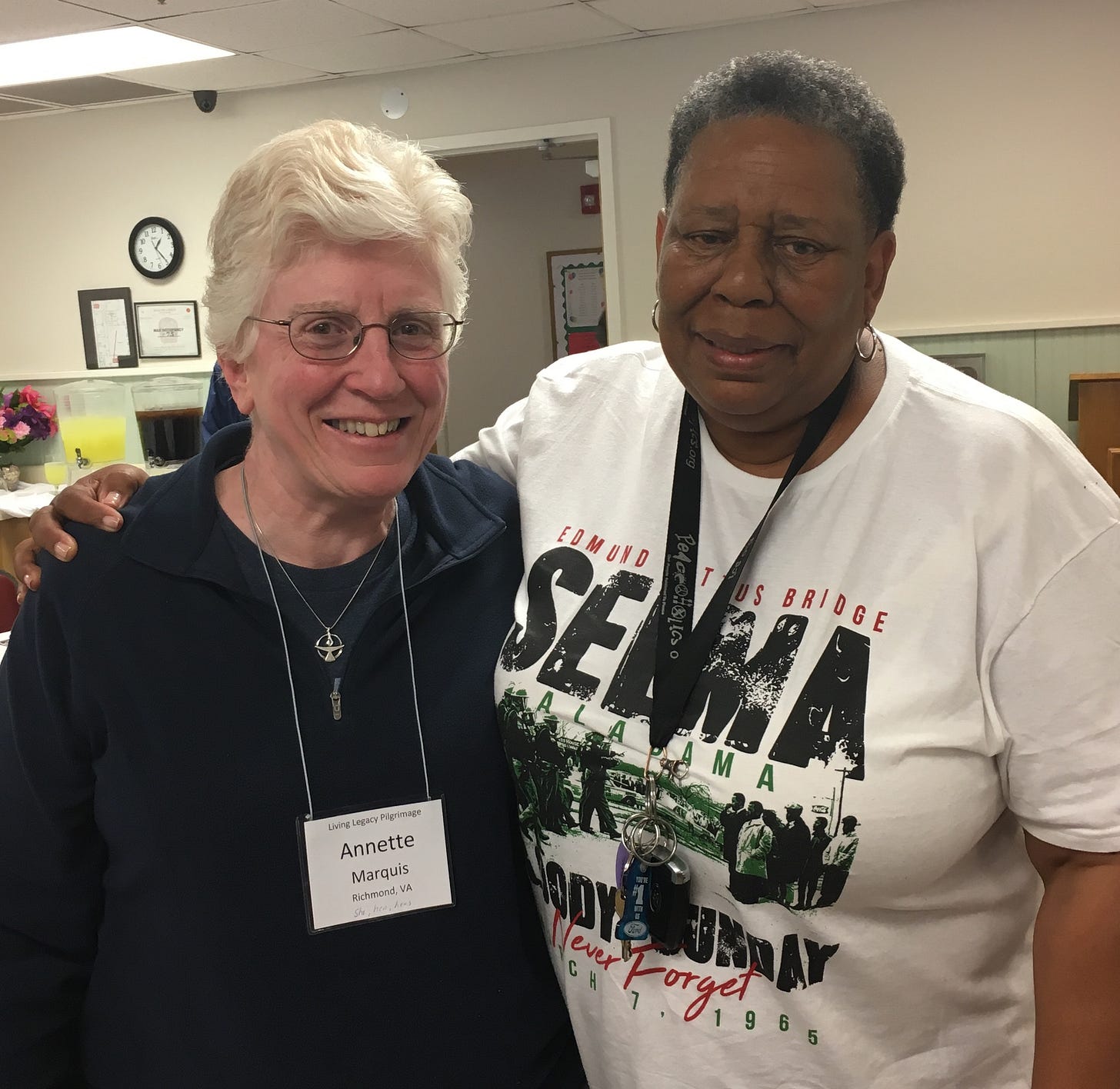

The organization I co-founded, the Living Legacy Project, brings busloads of people to Selma several times each year. Joanne is often the highlight of our trips, despite and maybe because of her no-nonsense way of interacting with the groups she meets.

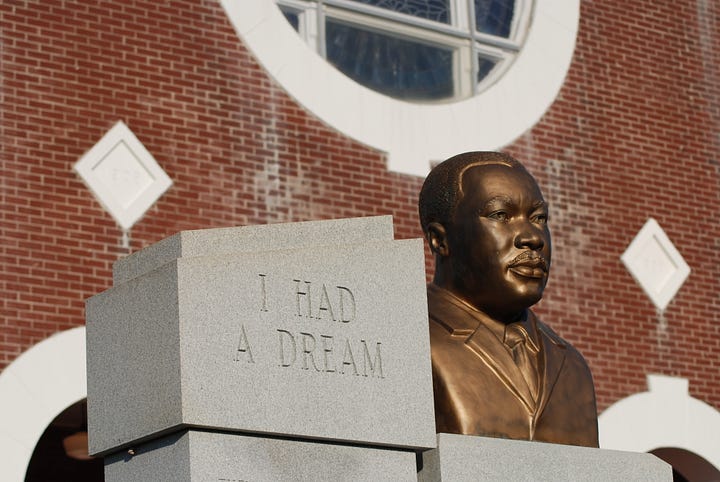

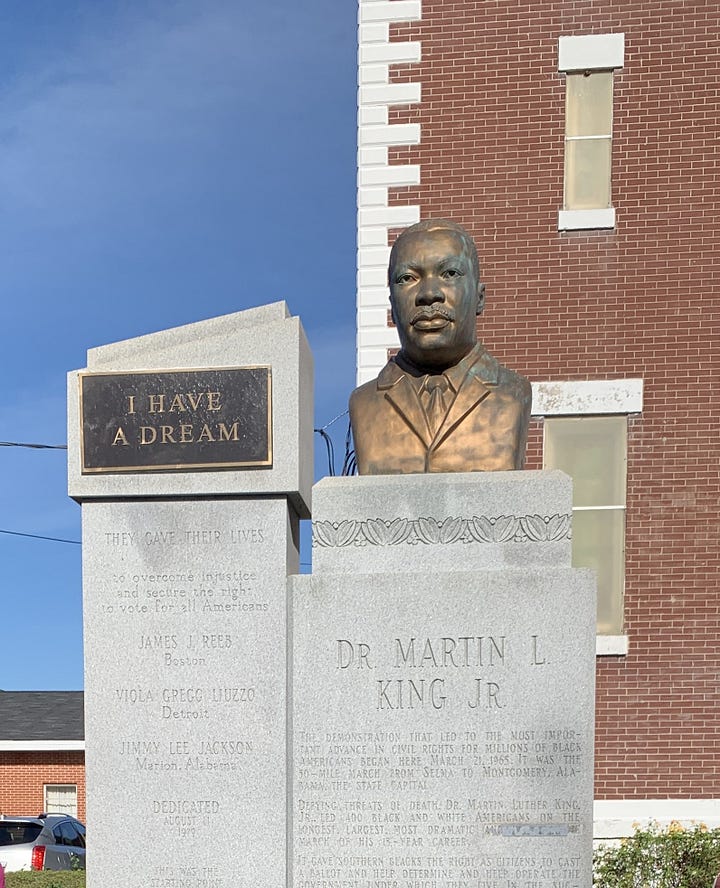

Standing in front of Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, the center of the Selma Voting Rights Movement, Joanne orders the members of our group to look at the Martin Luther King, Jr. monument in front of the church.

“Look up there. What’s wrong with this monument?” she asked as she points to the image of Dr. King, a look of disgust on her face. “What’s wrong with this? Anybody?”

After a few uncomfortable moments, one brave woman offers, “It says, ‘I had a dream’,”

“You win the prize,” Joanne says pointing to the woman. “What kind of message is that to the young people growing up in these projects across the street?” “I had a dream? What does that say to those children?”

Although it took many years of advocacy by Joanne and the tour groups she inspired, the monument has finally been corrected to inspire the hope Martin Luther King, Jr. intended with his words, “I have a dream.”

I’m happy to say that as I traveled there with numerous groups of pilgrims, Joanne and I have become friends, a friendship based on mutual respect for the work we do and our commitment to keep doing it no matter what.

It’s because of people like Joanne that I continue to accompany people to Selma—that I keep telling the stories of the Civil Rights Movement. Joanne’s drive to ensure that every child can dream and make their dreams come true inspires me to keep going, to not get too discouraged, and to keep fighting even the seemingly small battles—like changing the words on a monument.

Next post: