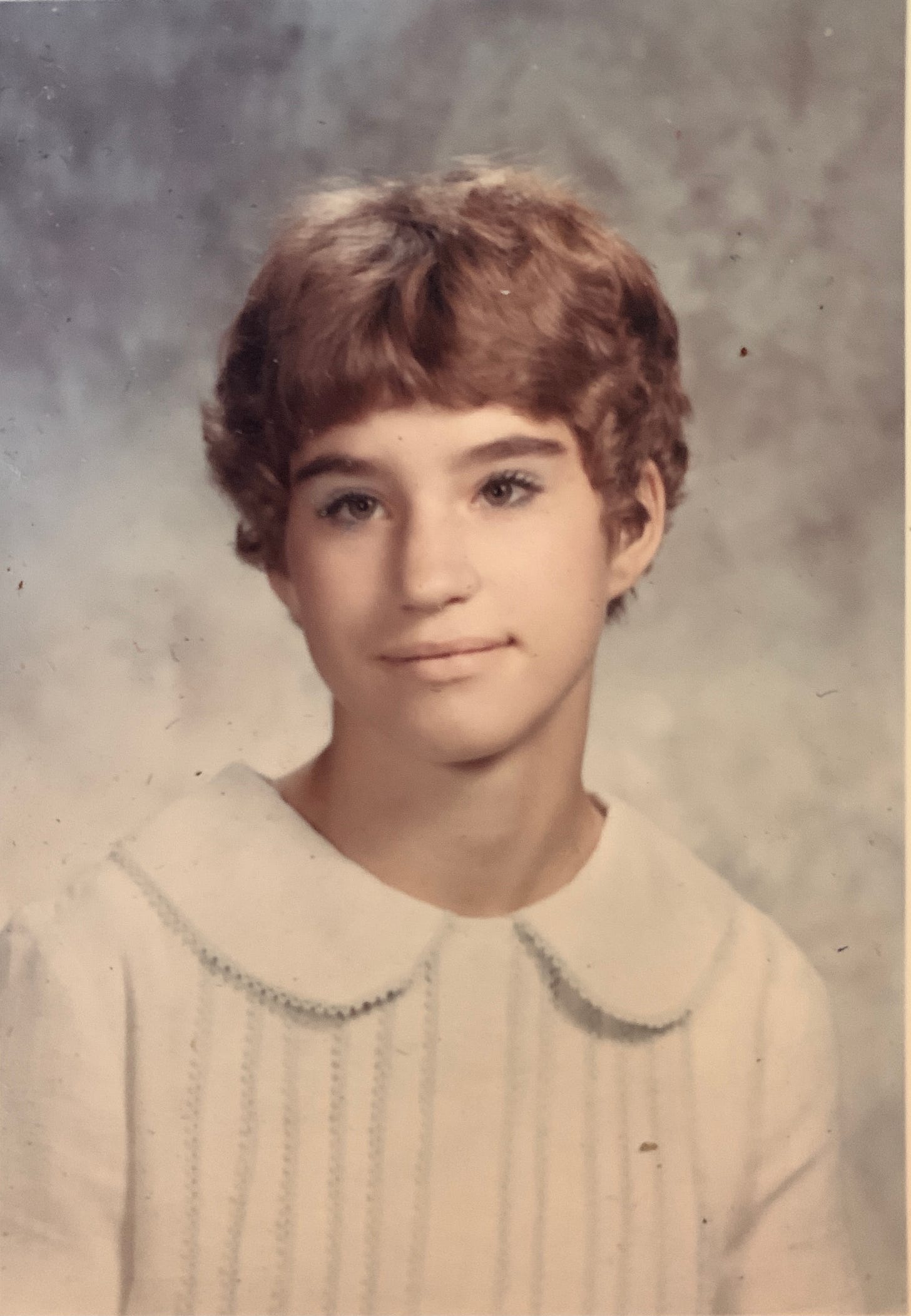

In 7th grade, I left my small, three-room Catholic schoolhouse and ventured into the public junior high. When I did, I developed a new set of friends. Susan was one of them. She was smart and loved English—two qualities that instantly attracted me to her. She was different from my Catholic school friends. She had confidence in who she was—she could focus on her schoolwork and still enjoy having fun. I admired that about her. We played in Beaver Lake where she lived, had sleepovers, experimented with the contents of her dad’s liquor cabinet, got too sunburned falling asleep on a raft on the lake, and enjoyed being kids.

While we were still in junior high, Susan came home from school to discover that her mother had died. As tragic as that news was, it became even more tragic in my mind when my mother who had heard from a friend of hers that she died by suicide. As a result of this Accidental Mentors project, I learned from Susan that this rumor was untrue. Instead, her mother died from a massive coronary. How the myth of a death by suicide got started, I’ll never know. I just know that I’ve believed it my entire life and knowing something like this about a dear friend, even if it wasn’t true, has had a life-long impact on me.

I didn’t know much about suicide then—what teenager who hasn’t been directly impacted by it does? On the days that followed, my mother talked with me about the impact of suicide on a family, so I thought that I knew a little of what my friend was going through.

Susan handled her mother’s death with grace, at least publicly, but I could feel her unspoken pain. We never talked about it. If we had, I might have learned much sooner about her actual cause of death. Regardless of the cause, though, I struggled with what to do or say to help.

A short time after her mother’s death, Susan, her father, and younger sister, moved to Fort Smith, about eighty miles from Rogers. We stayed in touch for a while—I even ran away to her house one time—but gradually, we drifted apart. I imagine that my own discomfort with how to help played a part in that.

Years later, on September 11, 2001, the day of the World Trade Center and related attacks, I was working as the Executive Director of Third Level Crisis Center, a mental health crisis center located in Traverse City, Michigan. We served much of Northern Michigan’s Lower Peninsula and had developed a year-long plan to connect our crisis lines to the national 1-800-SUICIDE hotline. Then I received a call that changed everything. The people at this national hotline anticipated that because of the day’s events, they would be overrun by calls and asked if we could come online sooner than scheduled to handle some of them. Like, TODAY!

It was an impossible request. In addition to the technical details that had to be worked out, we had to ensure that our mostly volunteer staff had the training they needed to respond knowledgably to the calls we might receive. How could we do this so quickly and do it well?

I went into my office and closed the door to consider the request. For reasons I didn’t understand in the moment, memories of Susan flooded my thoughts. They surprised me at first. I hadn’t seen or spoken to Susan in years. I didn’t grasp the connection. Then it all came flooding back—the helplessness I felt so many years before when I learned of her mother’s death. Believing that she had died by suicide, I couldn’t reconcile her actions then, just like I didn’t understand the events of this day. And just like this day, I didn’t know how to help.

I let the feelings—all the feelings, the ones from the horrific events of this day and from my first encounter with death by suicide—wash over me. Behind a closed office door, I cried. Although the two events seemed so disconnected, feelings of desperation and despair linked them across the decades. In that moment, I understood the anguish a person who contemplates suicide feels in ways I never had before. I doubled over with an overwhelming sense of desolation and despair and rocked myself trying to find my equilibrium.

At that moment, I decided to dedicate my work to Susan and her family, to do whatever I could to offer hope to people contemplating death by suicide and offer solace to those who were left behind. I made a call to the national hotline director and told them yes. We would do all we could to be ready.

By the end of the day—that same day--calls from our geographic area to 1-800-SUICIDE rang on Third Level’s phones. Although thankfully not the onslaught that the national hotline had feared, people who needed our help began to call. Our volunteers and paid staff stepped up and handled the calls with competence and care. I trust that the people who called that day, overwhelmed by grief and desperation from the day’s events, found hope from the person they talked with and were able to keep on living for another day.

I never told Susan this. I didn’t feel a need to tell her, and even if I had, I didn’t know where she was and had no way to reach her in the days before Facebook. It was one of those private moments that has stayed with me though, when life events remind me that how we inspire someone is often never known. I didn’t know Susan’s mother well, and, in fact, I didn’t even know Susan that well.

If we had stayed in touch, I might have learned sooner about the myth I carried all my life about how her mother died. As it was, what I thought I knew about them made a difference to me and countless others who reached out for an empathetic ear and received one that day and for years to come.

Postscript: The 1-800-Suicide hotline has been recently resurrected as the 988 Suicide and Crisis Hotline. If you or a loved one is feeling despair and having suicidal thoughts, you can call 988 to reach a national network of support. Please spread the word about this important resource available for free to anyone who needs it.

Again, a stellar entry. Thank you.