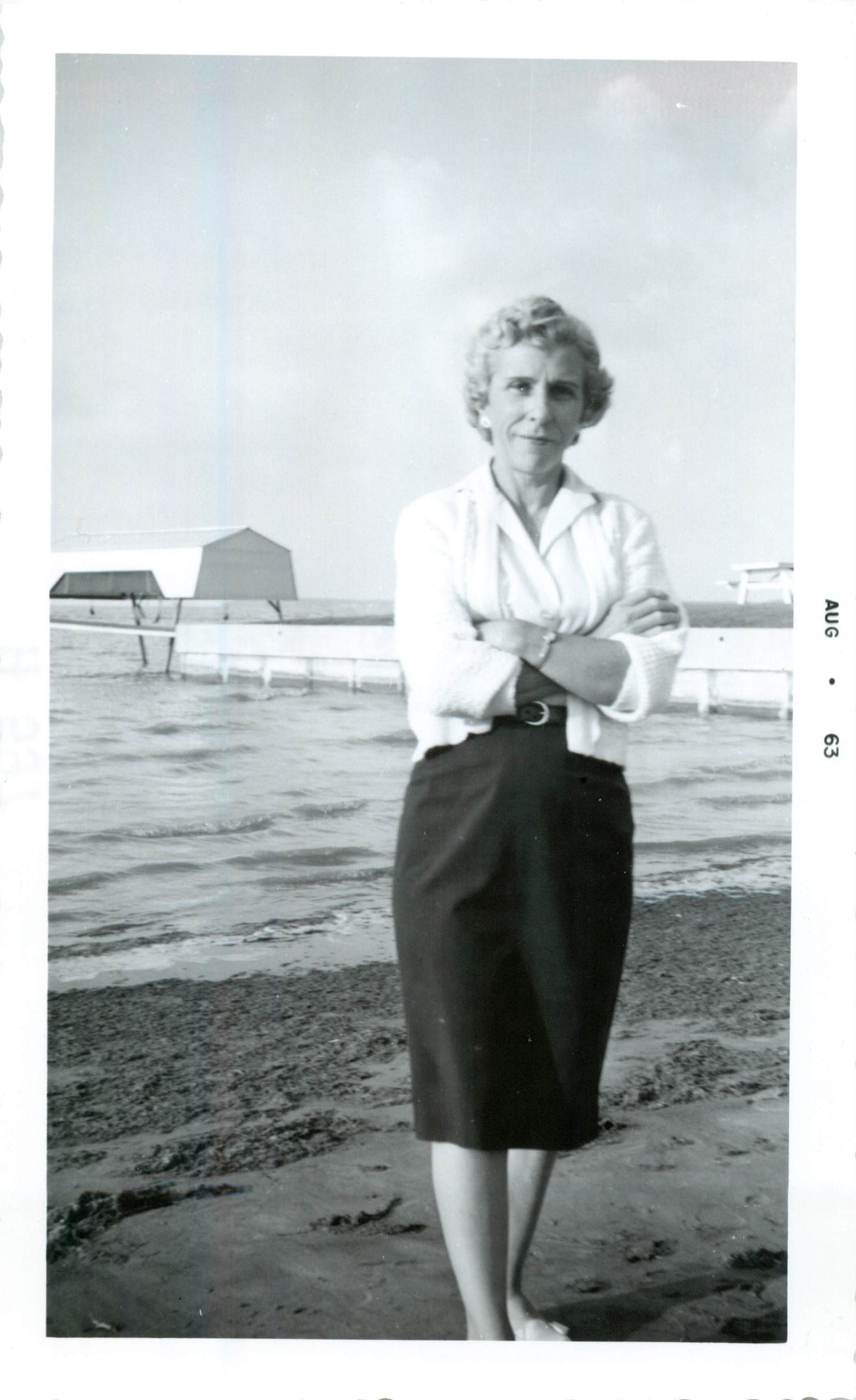

A Letter to Mom, #1

The first in a series of four letters I wrote to my Mom with stuff I couldn't/wouldn't/didn't say to her when she was alive.

Dear Mom,

You’ve been gone more than twenty years now and I still think of you every day. Most days, I wish I could call to catch up on our daily lives like we used to. I loved the way you could laugh at yourself and the situations you found yourself in—like the time you picked up the wrong line while working in the Sears Roebuck catalog department. Thinking you were talking to a woman about fencing, instead you asked a woman ordering bras if she wanted the kind that “stretched all the way around her property.”

Remember how you couldn’t stop laughing that day? I can still picture the yellow telephone hanging on the wall in the kitchen with the long cord that stretched all the way to my bedroom. I remember calling you at work that day when all you could do was stammer. “C, c, call, call you back,” you finally spit out, words punctuated by guffaws and shallow breathing.

I still see you riding the cable cars in San Francisco, and I can feel my anxiety as I thought about my 75-year-old mother hanging onto the outside of the car. You got seasick watching Sea Hunt on TV; the thought of you hanging onto the outside of a cable car terrified me. That’s why I carefully guided you to an inside seat for your first journey over Nob Hill and down to Fisherman's Wharf. But when I asked you how you liked the ride, you replied with a smile as wide as the Golden Gate, eyes gleaming like the sun bouncing off it, “It was great! But next time, can we ride on the outside?”

I have to say I was thunderstruck. But for the rest of our visit there, that’s what we did. To this day, I can’t see a cable car on TV without seeing you hanging on with one hand, waving with the other, and laughing all the way down to the wharf.

I think my sense of humor comes from you. I used to think it came from Dad, but now I realize that’s because I rarely gave you credit for anything. You were the subservient wife, a homemaker with no skills beyond cooking and cleaning. I never thought you were smart. I don’t remember what incident happened that caused us to nickname you, “Dummy” but, cruelly, we did. We even addressed your Mother’s Day and birthday cards that way. And in camaraderie, I embraced the moniker, “Little Dummy.” It took me years to fully embrace my intelligence. Maybe that was because Jarrett (my brother) had so much more book-smarts than I, but I now think this family “joke” played a part. I wonder what it did to you—a woman who possessed the ego and self-confidence of a snail.

You were obsessed with TV. And, as far as I could tell, had no interests, desires, or talents to occupy your time, so TV was all there was for you. When your work was done—the house clean, dinner put away, and the dishwasher running—you sat down in front of the television. On most nights, you stayed there until a disembodied male voice woke you from your dozing by announcing the station you were watching was signing-off for the night. The National Anthem lulled you to sleep too many nights to count.

For years, you didn’t read because you couldn’t see the words on the page. I finally figured out you were too vain to get glasses. Jarrett and Dad consumed science fiction like they were planning to be astronauts. When Dad returned home from his work travels, conversations about what they were reading, interspersed with animated discussions of football games and strategy, hummed alongside the ever-present television soundscape. When you eventually overcame your vanity and got reading glasses, the world changed for you, but I was already gone by then, so I never knew in what ways.

I don’t know if I respected you growing up. I respected you as my mother. That’s what good kids were expected to do back then. I never really knew you though. I knew what you expected of me. To be ladylike. To be polite. To not tattle. But the details of your life I gathered like the crumbs you swept up from the kitchen floor after hosting a dinner party for Dad’s co-workers.

As a grown woman now, some would say an old woman, I’ve come to believe that people have a right to their secrets. I would be a hypocrite if I believed differently. I’ve spent much of my life in the closet. Until I was in my forties, the fact that I was a lesbian was a closely guarded secret that I selectively revealed. You knew it, of course, but only after Sister Barbara Ann disclosed it to you, and then later, after failing to live straight, I told you myself that it wasn’t going away. You didn’t receive the news well. You believed my sexual orientation was punishment from God for your sins. You never told me what your sins were.

I always knew you had secrets, too. There was so much you wouldn’t talk about. “If you only knew,” you would say, but you never chose to enlighten me. I didn’t know your secrets were about me. I didn’t know you lied to me. I know that now and, I will tell you, it hurts. I imagine it’s a pain like the one you carried with you when you learned that I was not going to grow out of my love for women.

It’s been a few years now since I’ve learned as much as is knowable about your secrets. In that time, I’ve come to realize that my pain is not as much from you as it is about you. It’s from knowing the freedom of living in the truth—a freedom you never afforded yourself. I wish I could give that to you. I wish I could let you know that I know. I wish we could talk about it, so you could know I forgive you for lying to me about who I am.

I’m not saying I’ve come to this place easily. I’m not saying I not angry about what you did. I’m not saying I’m not hurt that you lied to me. I am saying that I wish you too could know the freedom that comes from living in the truth. I wish you still had the chance to forgive yourself. I even wish we could find a way to laugh about it. Something in it all must be funny.

Your (not dummy) daughter,

Annette

So touching!

Wow...you are an amazing writer. I look forward to keeping up with this journey. Intriging, thought provoking and very honest. I'm learning a lot, on how to find my own voice and confront my family secrets. Thank you so much for sharing this.